1905 Buongiorno Painting Found

mystery in the attic

Wonders never cease…as with an exotic and very old painting recently found in the attic of the Marland Grand Home. The historic house museum has recently gone through a conversion. A complete clean up for the 2016 centennial year has taken place with exhibits updated, labeled and cleaned, inventory listed, rooms and closets organized and freshened up, and the attic decluttered and swept out.

“As I was sifting through years of odd items in the attic space in preparation for roof repairs this fall, I came across a painting exposing it for further research”, said Jayne Detten, site supervisor. “The painting was listed in our inventory as a portrait of a Spanish-type caballero cowboy, which it does resemble at first glance. No other information, however, was included.”

Unbeknownst to any staff presently at the site, the painting had been done by an artist who emigrated from Naples, Italy, to New York City in the late 1800s.

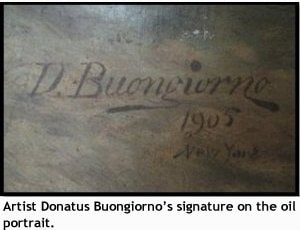

After further investigation following the lead of the artist’s signature, a chain of events unfolded. The name in the lower left hand corner, D. Buongiorno, was clear as was the date signed, 1905. The stretchers were old. They looked hand-made and bore no manufacturers stamp, as is common with stretchers today. Corners had wooden pieces jammed into wooden slots to make the canvas taunt; a past way of holding a frame together.

“The life-size painting was well done, said Detten, so I was longing to find out more about it.”

Who was this cowboy man, handsome and debonair standing tall and confident with leather chaps, gun and holster, neck scarf and cigar in hand?

“As I was sifting through years of odd items in the attic space in preparation for roof repairs this fall, I came across a painting exposing it for further research”, said Jayne Detten, site supervisor. “The painting was listed in our inventory as a portrait of a Spanish-type caballero cowboy, which it does resemble at first glance. No other information, however, was included.”

Unbeknownst to any staff presently at the site, the painting had been done by an artist who emigrated from Naples, Italy, to New York City in the late 1800s.

After further investigation following the lead of the artist’s signature, a chain of events unfolded. The name in the lower left hand corner, D. Buongiorno, was clear as was the date signed, 1905. The stretchers were old. They looked hand-made and bore no manufacturers stamp, as is common with stretchers today. Corners had wooden pieces jammed into wooden slots to make the canvas taunt; a past way of holding a frame together.

“The life-size painting was well done, said Detten, so I was longing to find out more about it.”

Who was this cowboy man, handsome and debonair standing tall and confident with leather chaps, gun and holster, neck scarf and cigar in hand?

internet research

Detten found a web site by searching the artist’s signature. Fortunately the great grandniece of the original artist, Janice Carapellucci, who lives in Brooklyn, New York, had put together several pages about her uncle Donatus Buongiorno’s history and work. Carapellucci had researched the painting thoroughly, but one missing element of the mysterious Squaw Man story remained - the painting itself. With all the intrigue of a mystery novel, the story of the cowboy painting began to coalesce.

Detten sent an email with a digital copy of the painting to Carapellucci. She immediately responded with great joy and enthusiasm.

“This is it! This is the painting I’ve been looking for for 10 years! I wasn’t even sure what it looked like.” She continued, “Check the back and see if these are any notes on the stretchers, frame or canvas.”

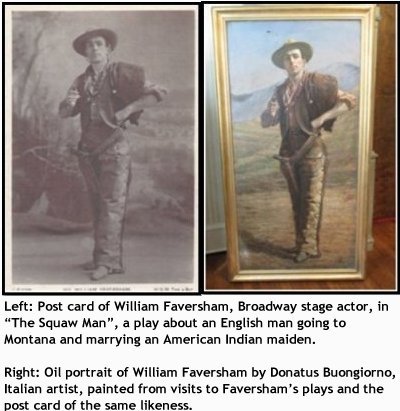

Detten looked and written on the back side of the canvas stretcher along the top edge in pencil was the title “The Squaw Man”. The penmanship matched the penmanship of the artist signature perfectly. Carpellucci also sent a link to a period postcard of the subject which matched the artwork precisely and her web site continued to reveal more information on both the artist and the man in the painting.

Detten sent an email with a digital copy of the painting to Carapellucci. She immediately responded with great joy and enthusiasm.

“This is it! This is the painting I’ve been looking for for 10 years! I wasn’t even sure what it looked like.” She continued, “Check the back and see if these are any notes on the stretchers, frame or canvas.”

Detten looked and written on the back side of the canvas stretcher along the top edge in pencil was the title “The Squaw Man”. The penmanship matched the penmanship of the artist signature perfectly. Carpellucci also sent a link to a period postcard of the subject which matched the artwork precisely and her web site continued to reveal more information on both the artist and the man in the painting.

D. Buongiorno - The artist

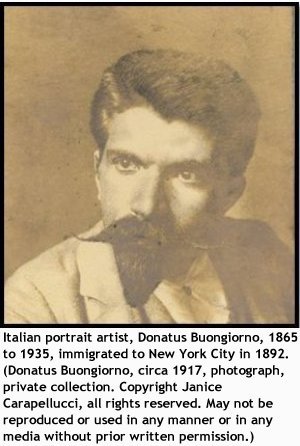

Donatus Buongiorno was born in Solofra, Avellino, moving to Naples in the 1800s to attend the Academy of Fine Arts of Napoli. Buongiorno also taught there in his later years. In 1892 he immigrated to New York and became a naturalized American citizen. There he worked as designer in a wallpaper factory and also painted murals for Catholic churches and portraits on the side. Buongiorno took on several important commissions, one being of President William McKinley. His work was at one time accepted to the prestigious competitive annual exhibit of the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia. During his lifetime Buongiorno traveled back and forth from the U.S. to Italy time and time again, all-the-while continuing to create his artwork.

william haversham - the actor

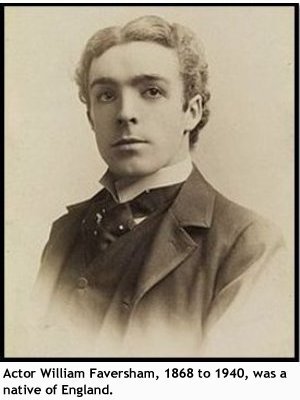

The painting’s subject, William Faversham, was an enormously popular and successful theater actor on Broadway in the early 1900s. Faversham was born in 1868 in England and was theatrically trained in London. He held over 70 starring roles such as Julius Creaser, Othello, and Hamlet. The term “Matinée Idol” was coined after Faversham as his matinee performances were numerous and very popular. The actor was one of the first to both act in and manage his own career. According to the Herald Tribune it was said he produced more plays in his day than any other producer/director in the United States with the exception of George M. Cohen. However, despite his huge stage success, the good-looking Faversham being quite high on his own merits was not much of a businessman. This characteristic proved to be self-defeating in later years.

the squaw man

“The link to the old post card of the actor dressed as the Squaw Man for sale on line made it clear that the actor and the man in the painting were one in the same, in fact identical.”, said Detten. “I immediately purchased the post card for our collections.”

Faversham produced, directed and starred in the production of “The Squaw Man” as reflected in the painting which shows Faversham clothed in his western costume for the starring role. The long-running Broadway play, 222 performances between 1905 and 1906, was immensely successful and was eventually made into a movie by Cecil B. DeMille.

The dramatic play begins in England at the home of Capt. James Wynnegate played by Faversham. Capt. Wynnegate leaves England for the Wild West of Montana where the Ute Indian maiden, Nat-u-ritch, saves his life. Nat-u-ritch and the captain fall in love, get married and have a son, Little Hal. Due to the relationship being a mixed-marriage, Hat-u-ritch must leave Wynnegate (now called Jim Carson). Wynnegate and son return to England where the captain reunites with his first love whose husband has recently died.

Faversham produced, directed and starred in the production of “The Squaw Man” as reflected in the painting which shows Faversham clothed in his western costume for the starring role. The long-running Broadway play, 222 performances between 1905 and 1906, was immensely successful and was eventually made into a movie by Cecil B. DeMille.

The dramatic play begins in England at the home of Capt. James Wynnegate played by Faversham. Capt. Wynnegate leaves England for the Wild West of Montana where the Ute Indian maiden, Nat-u-ritch, saves his life. Nat-u-ritch and the captain fall in love, get married and have a son, Little Hal. Due to the relationship being a mixed-marriage, Hat-u-ritch must leave Wynnegate (now called Jim Carson). Wynnegate and son return to England where the captain reunites with his first love whose husband has recently died.

Law Suit

Carpellucci knew the painting existed because it had been involved in law-suit in 1908 in New York, Buongiorno vs. Faversham. Faversham, who commissioned the work (or his valet did for him), chose not to pay for the life size portrait at time of delivery, so Buongiorno sued him for what was due. A 1908 story in the New York Times, typical of the anti-immigrant bias in some journalism of the day, attempted to make Buongiorno look illegitimate and cast suspicion on the veracity of the commission.

Carapellucci pointed out that a more skeptical reader would wonder, “Was Buongiorno trying to extort $500 out of Faversham on a flimsy claim that the painting had been commissioned? Or was the actor trying to use his fame to wiggle out of a legitimate deal?”

Carapellucci believes that upon delivery of the painting, the actor simply chose to lie about the work and not pay because another New York Times story published a month after the first reports that Buongiorno won the settlement in the law-suit. The court awarded the artist $29 for the painting payment plus an undisclosed amount for costs. In today’s dollars the $29 would amount to approximately $500-$1000.

The actor made and lost several fortunes in his lifetime. In his later years Faversham declared bankruptcy twice and died penniless in a home for indigent actors, which seems to support the theory that Faversham’s case was a sham.

Carapellucci pointed out that a more skeptical reader would wonder, “Was Buongiorno trying to extort $500 out of Faversham on a flimsy claim that the painting had been commissioned? Or was the actor trying to use his fame to wiggle out of a legitimate deal?”

Carapellucci believes that upon delivery of the painting, the actor simply chose to lie about the work and not pay because another New York Times story published a month after the first reports that Buongiorno won the settlement in the law-suit. The court awarded the artist $29 for the painting payment plus an undisclosed amount for costs. In today’s dollars the $29 would amount to approximately $500-$1000.

The actor made and lost several fortunes in his lifetime. In his later years Faversham declared bankruptcy twice and died penniless in a home for indigent actors, which seems to support the theory that Faversham’s case was a sham.

post script

Though the New York Times story says Faversham rejected the painting initially, it’s suspected that he would have taken possession of it after he was ordered to pay for it in the judgment.

Before Carapellucci knew of the painting in Ponca City she hypothesized years ago to family members, “Presumably, he destroyed it, but being a theatrical man, he might have kept it to show to friends. …Alas the painting is probably long gone, but it may turn up at an auction or in a yard sale. From other portraits he painted, I know Buongiorno was capable of creating a recognizable likeness, so look for it!”

No one knows what became of the work after Faversham took possession. How did it come to reside in the attic of the MGH? Teddy Rahlf, maintenance man at the Marland Grand Home, remembers the work hanging on the 3rd floor stairwell about twenty years ago. Sometime after that point it was taken down and stored in the attic.

There is no evidence that E.W. Marland who built the house in 1916 owned the painting. The Marland family lived at the site until 1928. At that time they had a big yard sale selling off the smaller pieces that were inappropriate for their new 55-room palatial home, the Marland Estate on Monument. Pat (Paris) Moore, whose family lived at the site from 1940 to 1967, doesn’t recall the painting at all. It most likely came into the hands of the City of Ponca City, possibly during the 1917 to 1967 period, when the City Auditorium was housed at what is now the City Hall Commission Chamber.

“Plays were put on at the Civic Center auditorium through the years. I have been told that various art works hung at the auditorium, so the painting could have been at that location for a time,” said Detten. “When the city purchased the Marland Grand Home in 1967 the building was intended for use as the town’s cultural center home for works of art. The painting may have been moved to this site from another location.”

If you have any information about the “Squaw Man” painting, please contact Jayne Detten at the Marland Grand Home at 580-763-4580. More of Donatus Buongiorno’s work can be found at donatusbuorngiorno.com.

Before Carapellucci knew of the painting in Ponca City she hypothesized years ago to family members, “Presumably, he destroyed it, but being a theatrical man, he might have kept it to show to friends. …Alas the painting is probably long gone, but it may turn up at an auction or in a yard sale. From other portraits he painted, I know Buongiorno was capable of creating a recognizable likeness, so look for it!”

No one knows what became of the work after Faversham took possession. How did it come to reside in the attic of the MGH? Teddy Rahlf, maintenance man at the Marland Grand Home, remembers the work hanging on the 3rd floor stairwell about twenty years ago. Sometime after that point it was taken down and stored in the attic.

There is no evidence that E.W. Marland who built the house in 1916 owned the painting. The Marland family lived at the site until 1928. At that time they had a big yard sale selling off the smaller pieces that were inappropriate for their new 55-room palatial home, the Marland Estate on Monument. Pat (Paris) Moore, whose family lived at the site from 1940 to 1967, doesn’t recall the painting at all. It most likely came into the hands of the City of Ponca City, possibly during the 1917 to 1967 period, when the City Auditorium was housed at what is now the City Hall Commission Chamber.

“Plays were put on at the Civic Center auditorium through the years. I have been told that various art works hung at the auditorium, so the painting could have been at that location for a time,” said Detten. “When the city purchased the Marland Grand Home in 1967 the building was intended for use as the town’s cultural center home for works of art. The painting may have been moved to this site from another location.”

If you have any information about the “Squaw Man” painting, please contact Jayne Detten at the Marland Grand Home at 580-763-4580. More of Donatus Buongiorno’s work can be found at donatusbuorngiorno.com.

Students study exhibit

Oklahoma state university students

During the spring semester of 2017, two university students from the anthropology department of Oklahoma State University, Tanner Wiseman and Jeanie LaFon, are examining, studying and researching native tribal archaeological artifacts at the Marland Grand Home. Items from the Bryson-Paddock and Deer Creek excavation sites north of Ponca City along the Arkansas River are being studied and organized with the help of the interns. The students are learning about items that were excavated in an archaeological dig funded by E.W. Marland in 1926”, said Jayne Detten, Asst. Director of the Marland Grand Home and Marland Estate and supervisor of the site. “The excavation was led by Dr. Joseph P. Thoburn of the Oklahoma Historical Society.”

The excavation unearthed items from “Ferdinandina”, a 1700s Wichita tribal encampment where buffalo and deer hides were processed. The furs and leather items were then traded to the French who had sailed up the Arkansas River from New Orleans. “The artifacts were in a state of flux and had not yet been collected into one exhibit in our museum”, said Detten. “It was important to do that and the students are helping out.”

The students are also writing labels and story boards with descriptions to address the artifacts. The story boards will be added to the exhibit for explanation.

“The university regularly places students at museums and other public sites around the state”, said Detten. “We are very lucky to have these students assigned to our site. Our staff is limited in number and time concerning what we can accomplish, so it’s most helpful to have the input of the interns who are students in the field. In turn, each intern is gaining valuable knowledge of the artifacts and the people associated with them which is part of their required learning.”

Working through OSU under Dr. Stephen Perkins, Associate Professor in Social Anthropology, the students will receive class credit for their experience. Dr. Perkins incorporates the Bryson-Paddock and Deer Creek archaeological investigations into his class curriculum. In June, both students will be participating in a field school with Dr. Perkins at the Deer-Creek site for further class credit.

The students will also be creating a public “Listen and Learn” power point presentation on the 1926 Marland-Thoburn Excavation which will be presented later in the spring. The power point will tell the story of the excavation and show the artifacts found there. The students will be available at the time of presenting to discuss their experiences at the Marland Grand Home and the excavation findings with the public as well.

Later in the semester the students will be helping assemble a “Touch and Feel” hide exhibit which will contain parts of the deer used in the Native American lifestyle. This exhibit will be assembled from start to finish by the interns and supervised by Detten. A corresponding exhibit will include a museum case display of tools used to clean the hides and other related tools which are now in storage will also be developed.

To complement the student‘s efforts and showcase the new hide and tool exhibits, Detten is creating a fictitious 1700s “travel journal” activity to be used by younger students in grades 4th and up which will coordinate with the Marland-Thoburn artifacts and the new hide exhibits. Taking their journal along while exploring the museum, Marland Grand Home visitors will pretend they are a French fur trader traveling up the Arkansas River to Ferdinandina to do business with the Wichita Indians for furs and leather. The journal will take the guests to four locations within the Marland Grand Home where at each stop they will answer five questions about each location. The stops included the Marland-Thoburn exhibit case of excavated items, a large Ferdinandina painting, the Touch and Feel exhibit of deer parts and the new cased exhibit of tools used to tan and prepare the hides.

The excavation unearthed items from “Ferdinandina”, a 1700s Wichita tribal encampment where buffalo and deer hides were processed. The furs and leather items were then traded to the French who had sailed up the Arkansas River from New Orleans. “The artifacts were in a state of flux and had not yet been collected into one exhibit in our museum”, said Detten. “It was important to do that and the students are helping out.”

The students are also writing labels and story boards with descriptions to address the artifacts. The story boards will be added to the exhibit for explanation.

“The university regularly places students at museums and other public sites around the state”, said Detten. “We are very lucky to have these students assigned to our site. Our staff is limited in number and time concerning what we can accomplish, so it’s most helpful to have the input of the interns who are students in the field. In turn, each intern is gaining valuable knowledge of the artifacts and the people associated with them which is part of their required learning.”

Working through OSU under Dr. Stephen Perkins, Associate Professor in Social Anthropology, the students will receive class credit for their experience. Dr. Perkins incorporates the Bryson-Paddock and Deer Creek archaeological investigations into his class curriculum. In June, both students will be participating in a field school with Dr. Perkins at the Deer-Creek site for further class credit.

The students will also be creating a public “Listen and Learn” power point presentation on the 1926 Marland-Thoburn Excavation which will be presented later in the spring. The power point will tell the story of the excavation and show the artifacts found there. The students will be available at the time of presenting to discuss their experiences at the Marland Grand Home and the excavation findings with the public as well.

Later in the semester the students will be helping assemble a “Touch and Feel” hide exhibit which will contain parts of the deer used in the Native American lifestyle. This exhibit will be assembled from start to finish by the interns and supervised by Detten. A corresponding exhibit will include a museum case display of tools used to clean the hides and other related tools which are now in storage will also be developed.

To complement the student‘s efforts and showcase the new hide and tool exhibits, Detten is creating a fictitious 1700s “travel journal” activity to be used by younger students in grades 4th and up which will coordinate with the Marland-Thoburn artifacts and the new hide exhibits. Taking their journal along while exploring the museum, Marland Grand Home visitors will pretend they are a French fur trader traveling up the Arkansas River to Ferdinandina to do business with the Wichita Indians for furs and leather. The journal will take the guests to four locations within the Marland Grand Home where at each stop they will answer five questions about each location. The stops included the Marland-Thoburn exhibit case of excavated items, a large Ferdinandina painting, the Touch and Feel exhibit of deer parts and the new cased exhibit of tools used to tan and prepare the hides.